Mebendazole in Global Health Fighting Parasitic Infections in Low Income Countries

In the global fight against parasitic infections, neglected diseases particularly prevalent in low-income countries, Mebendazole stands as a stalwart ally. This humble yet potent medication has been pivotal in preventive chemotherapy efforts, marking significant strides in mitigating the burden of neglected tropical diseases. As we delve into the intricate web of parasitic infections and the multifaceted challenges they pose to global health, it becomes increasingly evident that Mebendazole plays a pivotal role in this narrative.

With an array of parasitic infections such as schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminthiases, and neglected intestinal parasites afflicting millions worldwide, the urgency for effective interventions has never been more pronounced. Against this backdrop, Mebendazole emerges as a beacon of hope, offering a cost-effective and readily accessible solution to combat these insidious diseases.

In this comprehensive exploration, we delve into the global landscape of parasitic infections, shedding light on the burden they impose on communities, particularly in low-income settings. We examine the mechanisms of action and efficacy of Mebendazole, delineating its crucial role in preventive chemotherapy campaigns orchestrated by global health organizations. Furthermore, we navigate through the challenges encountered in the implementation of Mebendazole treatment programs, acknowledging the intricate socio-economic and logistical barriers that impede its widespread dissemination.

As we traverse through the corridors of parasitic infections and global health initiatives, it becomes imperative to unravel the implications of Mebendazole utilization. From its impact on reducing infection rates to the emergence of resistance and safety considerations, we delve into the nuanced facets of Mebendazole-based interventions. Moreover, we scrutinize the cost-effectiveness of Mebendazole in the context of resource-constrained settings, evaluating its role in shaping public health policies and strategies.

Amidst the myriad challenges and complexities inherent in combating parasitic infections, Mebendazole stands as a testament to the power of accessible and affordable interventions in transforming the health outcomes of vulnerable populations. As we embark on this journey to unravel the intricate tapestry of parasitic infections and global health initiatives, let us illuminate the path forward, where Mebendazole continues to serve as a cornerstone in the relentless pursuit of a healthier, more equitable world.

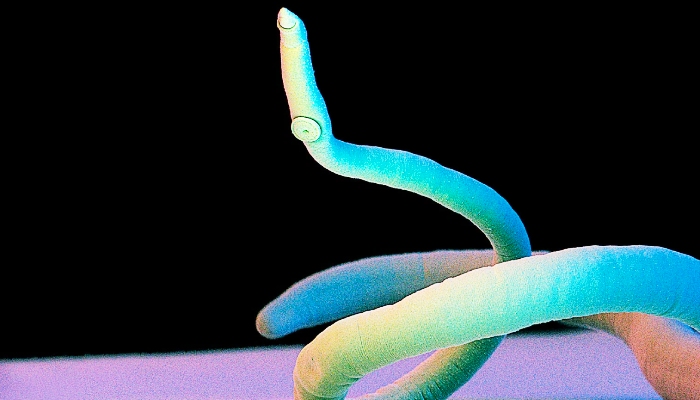

Helminth Infections

Helminth infections, prevalent in many regions, particularly in low-income countries, pose significant public health challenges due to their debilitating effects on affected individuals. These infections, caused by parasitic worms such as roundworms, whipworms, and hookworms, not only lead to a myriad of symptoms but also contribute to long-term health consequences and socio-economic burdens. In combating helminth infections, anthelminthic medications play a crucial role, with Mebendazole being a prominent agent in treatment interventions. The action of Mebendazole involves disrupting the parasites’ microtubule synthesis, thereby impeding their ability to absorb nutrients and immobilizing them, ultimately leading to their death.

This mechanism renders Mebendazole effective against various helminth species, making it a cornerstone in mass drug administration (MDA) campaigns aimed at reducing helminth infection rates and alleviating the burden of disease in endemic areas. However, challenges such as drug resistance and limited access to healthcare services persist, underscoring the need for comprehensive approaches encompassing improved sanitation, hygiene education, and sustainable healthcare infrastructure to effectively combat helminth infections and improve the well-being of affected populations.

The Global Progress of Soil-Transmitted Helminthiases Control in 2020 and World Health Organization Targets

Soil-transmitted helminthiases (STH), comprising infections caused by roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides), whipworms (Trichuris trichiura), and hookworms (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale), continue to pose a significant public health challenge worldwide, particularly in low-income countries. In 2020, concerted efforts were made to advance the control and elimination of STH infections, in alignment with the targets set forth by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The WHO has established ambitious targets to combat STH infections, aiming for the elimination of morbidity due to STH in children by 2030. These targets are grounded in evidence-based strategies encompassing preventive chemotherapy through mass drug administration (MDA), improved sanitation and hygiene practices, and health education initiatives targeted at at-risk populations.

Throughout the year, significant strides were made in developing countries scaling up preventive chemotherapy interventions, with a particular focus on reaching vulnerable populations in endemic areas. Mass drug administration campaigns, utilizing anthelminthic medications such as Mebendazole and Albendazole, were implemented in schools, communities, and health facilities to treat and prevent STH infections. These efforts were bolstered by enhanced surveillance systems and monitoring mechanisms to track progress and identify areas requiring intensified interventions.

Furthermore, innovative approaches were adopted to enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of STH control programs. Integrated interventions, combining deworming activities with other health initiatives such as nutrition programs and maternal healthcare services, were implemented to maximize impact and optimize resource utilization. Additionally, community engagement and empowerment strategies were employed to foster ownership and sustainability of control efforts at the grassroots level.

Despite these commendable efforts, challenges persist in achieving the WHO targets for STH control. Limited access to healthcare services, inadequate sanitation infrastructure, and socio-economic disparities continue to hinder progress in endemic regions. Moreover, emerging issues such as drug resistance underscore the need for continuous research and adaptation of control strategies to effectively address evolving challenges.

Looking ahead, sustained political commitment, multi-sectoral collaboration, and innovative approaches will be essential to accelerate progress towards the WHO targets for STH control. By leveraging lessons learned from past experiences and embracing a holistic approach to health promotion and disease control, the global community can strive towards a future where STH infections are no longer a threat to the well-being of vulnerable populations.

Burden of Disease due to Neglected Intestinal Parasites

Neglected intestinal parasites represent a significant burden of disease, particularly in low-income countries where access to healthcare and sanitation facilities is limited. These parasites, including species such as roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides), whipworms (Trichuris trichiura), and hookworms (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale), thrive in environments with poor sanitation and hygiene practices.

The impact of neglected intestinal parasites on public health is profound, manifesting in a range of debilitating symptoms and long-term health consequences. Chronic infections can lead to malnutrition, anemia, stunted growth, and impaired cognitive development, particularly in children. Moreover, intestinal parasites exacerbate existing socio-economic disparities, trapping affected communities in a cycle of poverty and ill-health.

The burden of disease due to neglected intestinal parasites extends beyond the immediate health consequences, encompassing broader socio-economic repercussions. In endemic regions, productivity losses stemming from illness and disability further strain already fragile economies, perpetuating the cycle of poverty and hindering socio-economic development.

Despite the profound impact of these neglected tropical diseases and intestinal parasites on global health, they often receive inadequate attention and resources compared to other infectious diseases. This neglect exacerbates the suffering of vulnerable populations and impedes efforts to achieve sustainable development goals related to health and well-being.

Addressing the burden of disease due to neglected intestinal parasites requires a multi-faceted approach encompassing preventive measures, access to essential healthcare services, and improvements in sanitation and hygiene infrastructure. Mass drug administration (MDA) campaigns with anthelminthic medications such as Mebendazole and Albendazole play a crucial role in controlling and preventing intestinal parasite infections. Additionally, investment in health education initiatives and community empowerment programs is essential to raise awareness and foster sustainable behavior change.

Survival of Parasite Eggs in the Environment

The survival of parasite eggs in the environment plays a crucial role in the transmission and persistence of parasitic infections, particularly in areas with inadequate sanitation and hygiene practices. Parasite eggs are resilient structures capable of withstanding harsh environmental conditions, enabling them to persist in soil, water, and other environmental reservoirs for extended periods.

Various factors influence the survival of parasite eggs in the environment, including temperature, humidity, soil pH, and exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. In favorable conditions, parasite eggs can remain viable for weeks to months, posing a continuous risk of infection to humans and animals.

Soil-transmitted helminths (STH) such as roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides), whipworms (Trichuris trichiura), and hookworms (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale) are particularly adept at persisting in the environment. Eggs shed in the feces of infected individuals can contaminate soil and water sources, leading to re-infection through ingestion or skin penetration.

The survival of parasite and eggs present in water bodies is of particular concern, as it can facilitate the transmission of waterborne parasitic infections such as schistosomiasis. Schistosome eggs released into freshwater bodies can hatch into larvae (cercariae), which infect humans through skin contact during activities such as swimming, bathing, or washing clothes.

In addition to soil and water, parasite eggs can also persist on contaminated surfaces and fomites, contributing to the spread of infection in households and communities. Poor sanitation practices, inadequate waste management, and limited access to clean water exacerbate the risk of environmental contamination and perpetuate the cycle of parasitic infections.

Effective control of parasitic infections requires not only treatment of infected individuals but also interventions aimed at reducing environmental contamination and interrupting transmission pathways. Strategies such as improved sanitation, provision of clean water, and health education initiatives play a crucial role in minimizing the survival of parasite eggs in the environment and mitigating the other risk factors of infection.

Furthermore, research into innovative approaches for environmental decontamination and parasite control, as well as community engagement and empowerment, are essential components of comprehensive parasitic disease control programs. By addressing the survival of parasite eggs in the environment, we can effectively combat parasitic infections and improve the health and well-being of vulnerable populations worldwide.

Implications of Intestinal Parasite Infections

Intestinal parasite infections have multifaceted implications for affected individuals and communities, ranging from immediate health consequences to broader socio-economic impacts. These implications extend beyond the physical manifestations of the infections and encompass various aspects of individuals’ lives and overall well-being.

Health Consequences

Intestinal parasite infections can lead to a spectrum of health issues, including gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and nausea. Chronic infections may result in malnutrition, anemia, stunted growth, and impaired cognitive development, particularly in children. Furthermore, severe cases can lead to intestinal obstruction, organ damage, and even death if left untreated.

Reduced Quality of Life

The symptoms associated with intestinal parasite infections can significantly impair individuals’ quality of life, leading to discomfort, pain, and distress. Chronic infections may limit individuals’ ability to participate in daily activities, attend school, or engage in work, thereby hindering their social and economic opportunities.

Impact on Education

Intestinal parasite infections are known to affect school-age children disproportionately, leading to absenteeism, decreased concentration, and poor academic performance. Chronic infections can impede children’s cognitive and physical development, and educational attainment, perpetuating cycles of poverty and limiting future opportunities.

Economic Burden

The economic burden of intestinal parasite infections is substantial, both at the individual and societal levels. Direct costs associated human infections and with healthcare seeking, diagnosis, and treatment can impose financial strain on affected individuals and their families, particularly in low-income settings where access to healthcare services may be limited. Additionally, indirect costs stemming from productivity losses due to illness and disability further exacerbate the economic burden, contributing to poverty and socio-economic disparities.

Stigma and Social Isolation

Intestinal parasite infections are often associated with stigma and social ostracization, particularly in communities where misconceptions about their transmission and prevention prevail. Individuals affected by these common infections worldwide may face discrimination and social exclusion, leading to feelings of shame, embarrassment, and isolation.

Interplay with Co-existing Conditions

Intestinal parasite infections can exacerbate the severity and complications of co-existing health conditions, such tropical diseases such as malnutrition, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis. Conversely, individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those living with HIV/AIDS, are more susceptible to severe intestinal parasitic infections, leading to adverse health outcomes and increased mortality rates.

Public Health Challenges

Intestinal parasite infections pose significant public health challenges, particularly in areas with inadequate sanitation and hygiene infrastructure. The persistent transmission of these infections perpetuates cycles of poverty and ill-health, hindering socio-economic development and impeding progress towards achieving global health goals.

Addressing the implications of intestinal parasite infections requires a comprehensive approach encompassing preventive measures, access to essential healthcare services, and improvements in sanitation and hygiene practices. By prioritizing interventions that target the root causes of these infections and promote sustainable behavior change, we can mitigate their adverse effects and improve the health and well-being of affected individuals and communities.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy refers to the use of drugs or medications to treat diseases, particularly cancer and certain infectious diseases caused by parasites. While chemotherapy is commonly associated with cancer treatment, it is also utilized in the management of various other parasitic diseases and infections, including those caused by protozoa and helminths.

In the context of parasitic infections, chemotherapy aims to eradicate or suppress the growth and reproduction of the parasites, thereby reducing the burden of disease and alleviating symptoms in affected individuals. The choice of chemotherapy agents depends on factors such as the type of parasite, the severity of the infection, drug efficacy, and potential side effects.

Anthelminthic medications are commonly used in the chemotherapy of helminthic infections, including soil-transmitted helminthiases (STH) such as roundworms, whipworms, and hookworms. Drugs such as Mebendazole, Albendazole, and Praziquantel are effective in treating these infections by either killing the parasites or preventing their ability to absorb nutrients or reproduce.

For protozoal infections such as malaria, leishmaniasis, and trypanosomiasis, chemotherapy involves the use of anti-parasitic drugs targeting specific stages of the parasite’s life cycle. For example, Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are recommended as first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria, while drugs such as Miltefosine and Sodium stibogluconate are used in the treatment of leishmaniasis.

Chemotherapy for parasitic infections may be administered orally, intravenously, or topically, depending on the medication and the nature of the infection. Treatment regimens often involve multiple doses over a specified duration to ensure the complete elimination of parasites and prevent recurrence of the infection.

While chemotherapy is an essential component of parasitic disease control programs, challenges such as drug resistance, limited access to medications, and potential adverse effects pose significant obstacles to effective treatment. Furthermore, the success of chemotherapy relies on comprehensive strategies that address underlying factors contributing to parasitic infections, including poverty, inadequate sanitation, and lack of access to healthcare services.

Soil-Transmitted Helminths: Strongyloides Stercoralis

Strongyloides stercoralis is a soil-transmitted helminth (STH) that infects an estimated 30 to 100 million people worldwide, primarily in tropical and subtropical regions. Unlike other STH species such as roundworms, whipworms, and hookworms, Strongyloides stercoralis has a unique life cycle characterized by both free-living and parasitic stages, contributing to its persistence and ability to cause chronic infections.

The life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis begins with the penetration of infective larvae into the human skin, usually through bare feet in contact with contaminated soil. Once inside the host, the larvae migrate to the lungs via the bloodstream, where they are coughed up and swallowed, eventually reaching the small intestine. In the small intestine, the larvae mature into adult worms, which produce eggs that hatch into larvae. Unlike other STH species, Strongyloides stercoralis has the ability to complete its entire life cycle within the human host, leading to autoinfection and the potential for chronic, long-term infections lasting decades.

Chronic Strongyloides stercoralis infections can result in a range of symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and respiratory symptoms such as cough and wheezing. However, many individuals infected with Strongyloides stercoralis may remain asymptomatic or experience mild symptoms, leading to underreporting and underdiagnosis of the infection.

Complications of chronic Strongyloides stercoralis infections can be severe, particularly in immunocompromised individuals such pediatric patients such as those living with HIV/AIDS or receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated strongyloidiasis, characterized by the widespread dissemination of larvae throughout the body, can lead to life-threatening complications such as sepsis, meningitis, and organ failure.

Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection is challenging due to the intermittent shedding of larvae in stool samples and the potential for low sensitivity of diagnostic tests. Serological tests such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of specific antibodies are commonly used for screening, while microscopic examination of stool samples may be used to visualize larvae.

Treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis infection typically involves the use of anthelminthic medications such as Ivermectin or Albendazole, administered orally for a specified duration. However, treatment may need to be repeated to ensure complete eradication of the infection, particularly in cases of chronic or hyperinfection syndrome.

Preventive measures to control Strongyloides stercoralis infection include promoting hygiene practices such as wearing shoes, practicing proper sanitation, and avoiding contact with contaminated soil. Additionally, community-based interventions such as health education and mass drug administration (MDA) may be implemented to reduce the prevalence of infection in endemic areas.

Schistosomiasis: Schistosoma

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, is a parasitic disease caused by several species of the genus Schistosoma. It is one of the most prevalent and significant parasitic infections worldwide, affecting millions of people in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in Africa, Asia, and South America. Schistosomiasis is considered a neglected tropical disease (NTD) and is associated with substantial morbidity, mortality, and socio-economic consequences.

There are several species of Schistosoma that can cause human schistosomiasis, including Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma haematobium, and Schistosoma japonicum, each with distinct geographical distributions and transmission cycles. These parasites have a complex life cycle that involves freshwater snail intermediate hosts and definitive mammalian hosts, including humans.

Transmission of Schistosoma occurs through contact with contaminated freshwater bodies, such as rivers, lakes, and irrigation canals, where infected snails release larval forms of the parasite (cercariae) into the water. Upon contact with human skin, cercariae penetrate the skin barrier and migrate through the bloodstream to various organs, where they mature into adult worms and produce eggs.

The eggs released by adult Schistosoma worms can cause tissue damage and trigger immune responses, leading to a range of clinical manifestations depending on the species intestinal worms involved and the organs affected. Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum primarily affect the intestines and liver, causing symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hepatosplenic inflammation. In contrast, Schistosoma haematobium primarily affects the urinary tract, leading to symptoms such as hematuria, dysuria, and urinary tract infections.

Chronic schistosomiasis can result in serious complications, including liver fibrosis, bladder cancer, kidney damage, and infertility. Moreover, schistosomiasis has significant socio-economic impacts, particularly in endemic regions where the serious disease burden contributes to poverty, malnutrition, and reduced productivity.

Diagnosis of schistosomiasis relies on various methods, including the detection of parasite eggs in stool or urine samples using microscopy, serological tests to detect specific antibodies, and molecular techniques for species identification. Treatment of schistosomiasis typically involves the use of anthelminthic medications such as Praziquantel, administered orally in a single dose or multiple doses depending on the severity of the infection.

Preventive measures to control schistosomiasis include improving access to safe water and sanitation, promoting hygiene practices such as avoiding contact with contaminated water, and implementing snail control measures in endemic areas. Additionally, community-based interventions such as mass drug administration (MDA) and health education programs play a crucial role in reducing the prevalence and transmission of schistosomiasis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, helminth infections, including intestinal nematode infections and intestinal helminth infections, represent a significant public health challenge worldwide, particularly in low-income countries where access to healthcare resources is limited. These parasitic infections, caused by various species of worms, inflict a heavy burden on affected individuals and communities, leading to a range of debilitating symptoms and long-term health consequences. Anthelminthic medications, such as Mebendazole and Albendazole, play a pivotal role in treatment interventions, with their action targeting the parasites’ ability to survive and thrive within the human host. However, the battle against helminth infections is far from over, as challenges such as drug resistance, inadequate healthcare infrastructure, and socio-economic disparities continue to impede progress.

Therefore, concerted efforts are needed to implement comprehensive control strategies encompassing preventive measures, access to essential medications like Mebendazole and Albendazole, and improvements in sanitation and hygiene practices. By addressing the root causes of helminth infections and fostering global collaboration, we can strive towards the elimination of these diseases as a public health threat and improve the health and well-being of vulnerable populations worldwide.